Omaha Bahais

First all Native American Local Spiritual Assembly

Omaha Nation - Macy Nebraska 1948

Left to right - Front row -Daisy Tyndall, Frank Tyndall, Paul Lovejoy, Henry Turner and Jennie Turner.

Left to right - back row - Suzette Morris, Paul Thomas and Eliza Thomas, Madeline Lovejoy.

Special thanks to Karen Jentz for identifying the members in this photo!

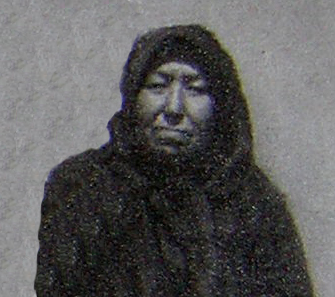

Mary Farley Stevison the first Omaha Baha’i declared on August 5, 1937.

Mary was born around 1884 to Rosalie LaFlesche Farley and Edward Farley. She married Dudley J. Stevison also Baha’i. She died on August 1,1959 in Sioux City, Iowa.

She served on the Baha’i Race Unity Committee while in Chicago in the 1940’s.

Grace “Hoo la ha mone” Walker Thomas Cline - Omaha Nation declared as a Baha’i on October 22, 1947 at the age of 65. Her husband Ed Cline also declared on October 22, 1947 She was the daughter of Noah “Lifting Tail” Walker and Mary Walker.

Jennie Woodhull Merrick Turner declared as a Baha’i on October 22, 1947 along with her husband Henry Furnas Turner. She served on the Omaha Local Spiritual Assembly in Macy, Nebraska

Jennie was born October 1890 to Spafford Woodhull and Lucy (Me-gra-tae) Harlan Woodhull.

She was first married to Frederick Merrick when she was in her early teens. They had two daughters and one son. Frederick died around 1918. Jennie married Henry Furnas Turner around 1919. They had one son John and a daughter Clema Ramona.

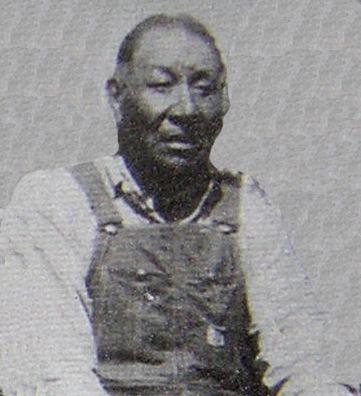

Henry Furnas Turner declared as a Baha’i on October 22, 1947 along with his wife Jennie Turner. He served on the Omaha Local Spiritual Assembly in Macy Nebraska.

Henry was born around 1883 and was the son of Oliver Gah-he-ga-gin-gab - Little Chief) and Me Meta. Henry died on March 19, 1949.

Levi (He'-con-thin'ke or White Horn) Levering declared as a Baha'i on October 22, 1947.

He was born around 1870. He attended Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania and another government school known as Bellevue College in Bellevue, Nebraska. He is recorded as stating that he was the first Indian named Levering. The name was probably given to him at one of the Boarding Schools. HIs birth name was He’-con-thin’ke or White Horn. He was a member of the Tapa (Deer) clan. He was a delegate from the Omaha Nation to Washington. He was a member of the Tribal Council and also known as an interpreter.

Paul Lovejoy declared as a Baha’i on October 22,

He was born around 1876. He married Amelia Tyndall who was also a Omaha Baha’i. Their daughter, Madeline was also Baha’i.

He was a mechanic for the Industrial Association in Omaha. He went to Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania and was on the first baseball team around 1880. He was a contributor for the book, Dance Lodges of the Omaha People: Building Memory by Mark Awakuni-Swetland and Roger Welsch.

Amelia Tyndall Lovejoy declared as a Baha’i on October 22, 1947

She was born around 1882 and died on April 11, 1963. She married Paul Lovejoy (Omaha Baha’i). Their daughter Madeline was also Baha’i.

Madeline Lovejoy - Omaha Nation Baha’i

Madeline Lovejoy was born in 1907 and was the daughter of Paul and Amelia Lovejoy. She served on the Omaha (Macy) Spiritual Assembly.

Eliza Thomas - Omaha Nation Baha’i

Eliza Morgan Thomas was born in 1879 to Ellis “Shongaska - White Horse” Blackbird and Pon-ca-sa. She married Paul “He-gra-gha” Thomas also an Omaha Baha’i.

Paul “He-gra-gha” Thomas - Omaha Nation Baha'i

Paul “He-gra-gha” Thomas was born February 24, 1876. He declared as a Baha’i on October 22, 1947. He married Eliza Morgan also an Omaha Baha’i.

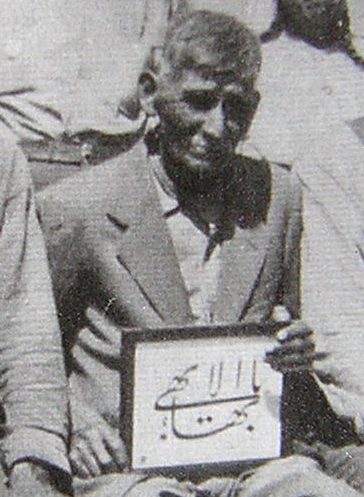

Eddie “Wahte” Cline Omaha Nation declared as a Baha’i on October 22, 1947. His wife Grace also declared on October 22, 1947 see separate document about her

Eddie “Wahte” Cline was born in 1876 to Mah wah danee (Henry Cline) and Me da ahbe. He married Ta e na in the very early 1900’s. She died a few years after their marriage (December 10, 1903) Their daughter died the previous month November 20, 1903. Their remaining children are Julia “Na Zae en ga” Cline and Henry Cline.

Around 1907 he married Grace “Hoo la ha mo ne” Walker Thomas. She was the daughter of Noah “Lifting Tail” Walker and Mary Walker. Together they had five daughters - Mary, Lucy, Grace, Carriabelle (Janet) and Naomi Cline

The following is a paper published in the American Anthropologist. Eddie Cline and Rosalie Farley (the mother of another Omaha Baha'i - Mary Farley Stevison) are a large part of this paper.

AMERICAN ANTHROPOLOGIST

THE SURVIVAL OF OMAHA SONGS

It was more than fifty years ago that Alice Cunningham Fletcher first recorded the songs of the Omaha. In 1941 I visited the Omaha on their reservation in Nebraska in connection with my study of Indian music for the Bureau of American Ethnology. I talked with three of Miss Fletcher's singers and obtained re-recordings of three of the songs which they had recorded for her.

Three groups of singers contributed to my work among the Omaha and seventy songs were recorded, with descriptions of their use. In the first group were those who had recorded for Miss Fletcher; in the second group were elderly men, who recognized many of Miss Fletcher's songs and recorded thirty-three interesting old songs with extended information concerning their use (they did not feel at liberty to record songs of societies to which they did not belong); the third group comprised younger men, who recorded songs connected with the first World War, in which they had served.

The three singers who had recorded songs for Miss Fletcher, and the only survivors of her work so far as could be ascertained, were Edward Cline, Benjamin Parker and Mattie Merrick White Parker. All were in excellent health and still active in various pursuits. The work with Cline was curtailed because the corn on his farm was ready to cut but he gave as much time as possible. He said that he "recorded for Miss Fletcher and Mr. La Flesche when they were together" and placed the time at the late eighties or early nineties. He re-recorded a "captive song" that he "sang for Miss Fletcher" and a song of the Tattooing ceremony. The words of the former are identical with those previously recorded but in the second-named song he used a different set of words from preference, explaining that he was, of course, familiar with the words in the published version. An adequate comparison of the renditions of these songs could be made only if the early phonograph records were compared with the dictaphone records made in 1941, but certain characteristics are readily noted. The captive song was sung much faster in the later rendition, with short phrases and frequent rests. This differs from the published version which resembles a solemn march, "words and music being closely woven about the thought of death." The opening phrase has the same intervals but the principal tones are accented differently. The trend of the closing measures is the same and it is evidently a variant of the same melody. The second song shows a greater difference from the published version, though there is a resemblance in the opening measures and the general trend of the melody is the same. These songs have not been sung for many years and it was said that very few men remain who know them. This suggests that the early form of ceremonial songs is being modified and that the songs will soon disappear.

Cline's description of the Tattooing ceremony was extended and interesting. He recorded three other songs of this ceremony and an old song of the Haethuska society that he learned from his father. He also recognized a scalp dance song presented by Miss Fletcher and explained the translation which refers to "Little Sioux." According to Cline this is one of many songs addressed to "Little Sioux," and referring to all the young men of the Sioux tribe. He said this song was about Flying Crow and "that is how the Little Sioux songs started." He said further that these were songs of "woman's war dancing" and not connected with the Haethuska, which was an old society of warriors.

The subject of the Wawan ceremony, which comprised an important part of Miss Fletcher's work, was not broached in 1941.

Benjamin Parker is not a member of what might be termed the ceremonial group of Omaha. He is a leader of the hand game and the writer attended a game held under his general direction. More than fifty Omaha were present and a majority took part in the game. At a subsequent time Parker recorded ten songs of this game, one being a song that he recorded for Miss Fletcher. He said the song is in common use at the present time and that "everybody knows it." The two versions differ only in a few bytones that are included in the early transcription. These are of no melodic importance and might occur in the singing of any song. The same words are now in use but Miss Fletcher presented the translation as "Little stone, what are you making?" while Parker translated the words as "Little stone, what do you want?" Parker described the origin of the game, saying it began as a contest of magic power but that the modern form is simply a game of skill. He recorded the only "obligatory song," with the words "Wakonda, our father, gave this to us." This was sung at the game attended by the writer and was followed by "songs of play." Other game songs recorded by Parker were very old. He related a legend of a "miracle boy," and recorded the song that is sung with the legend, he also told a story for children, containing two songs, the second having the words "I am muskrat, crying, somebody has taken my tail away." His recordings were twenty-two in number, this being the largest number recorded by an Omaha and including songs of the Tokalo and Haethuska, old societies described by Miss Fletcher. He recognized a scalp dance song presented by Miss Fletcher and recorded a different song of the same class. From this observation it appears that songs in use by many people are being accurately preserved, and that the old men have a clear memory of the history and early connection of the old songs.

An interesting group of songs recorded by Parker comprised five songs connected with the first World War. One was an old Haethuska song with modern words, and two were melodies composed after the return of the Omaha soldiers. It is interesting to note they did not "sing for the safety of the soldiers," as the Pawnee did during that war, also that Parker did not recall the use of magic in connection with the implements of the hand game, a custom related among the Choctaw. Mattie Merrick White Parker recognized a song that she recorded for Miss Fletcher, and her description of the song indicates it is the same. She said that she recorded for Miss Fletcher and Mr. La Flesche, that the recording was done at the home of Rosalie Farley, a sister of Mr. La Flesche living in Bancroft, and that "it must have been in 1890." She has not sung the song since that day, as she felt that she had given the song to them. The song belonged to her husband as a member of a certain sacred society, and he gave her the right to sing it because she shared with him a certain experience in a terrific storm, on the open prairie. She related the experience and described her husband's action, after which "the clouds broke as if cut with a knife and passed around us." Renewing these memories made her so sad that the questioning was not continued.

Four valuable old songs were recorded by Mattie Parker. One was a song that was sung when she underwent tattooing, in the ceremony described by Cline; another was a song given to her husband by a grizzly bear, this bear being the smallest of six that appeared to him in a dream; and another was a song that she composed about her dead brothers, who appeared to her in a dream. She said that she might sing this at a gathering and give a present, or someone else might sing it and she would give a present to the singers or to anyone she desired. In her eighty-ninth year, Mrs. Parker still "walks where she wants to go."

The custom of composing songs in honor of individuals is still observed by the Omaha. When John G. Miller returned from the first World War, his father composed both the words and melody of a song concerning one of his experiences. His father also gave him a name meaning Loud Thunder which occurs in the song. Miller does not sing this song himself and requested that it be recorded by his friend Robert Dale. When it is sung at a gathering, Miller rises, dances and gives presents.

Among the Omaha, as in other tribes, the opportunity for securing records and descriptions of old songs is rapidly disappearing but traditions still remain, with customs pertaining to tribal music.

FRANCES DENSMORE

RED WING, MINNESOTA

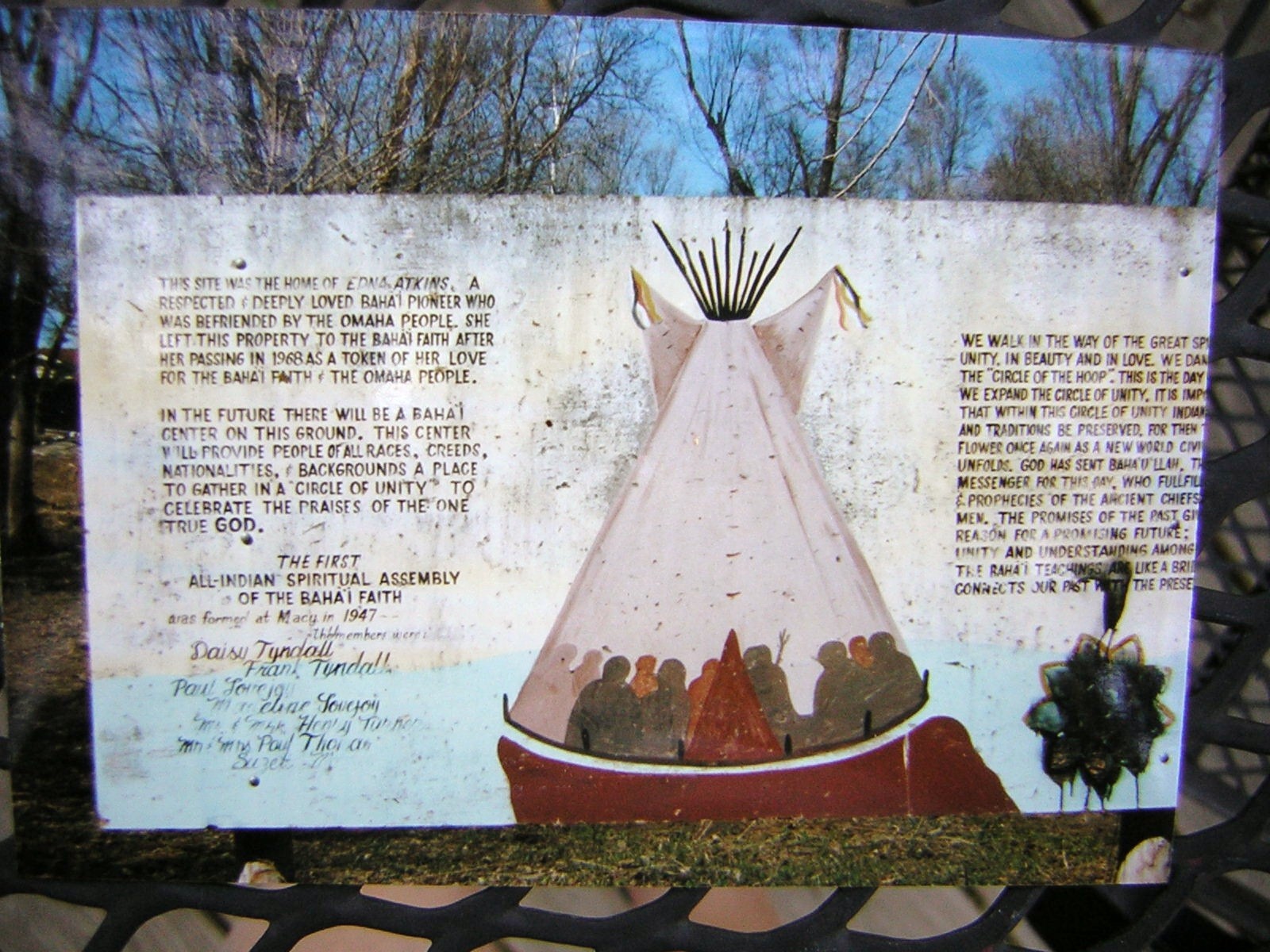

1966 - Sign in front of the Omaha Baha'i Center

Robert Big Elk was born in Macy, Nebraska and is of Omaha and Lakota/Dakota descent. He attended the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, New Mexico from 1963 to 1968. He studied under the renowned Hopi potter, Otellie Loloma, who taught him Indian traditional techniques and designs. He was a student at the University of Colorado

"I have always felt that I could make a most profound contribution to high standards of the art of pottery by synthesizing the beauty of design and cultural expressions of the many diverse and indigenous peoples. To this end I have spent much of my professional career visiting and researching the pottery and arts of tribes in the Southwest, the Plains, the Northeast, the Northwest and in California. Sitting beside the potters, carvers, painters and sculptors of these diverse tribes, I have learned new techniques that are often ancient techniques and have absorbed an appreciation of the cultural and artistic expression of many indigenous peoples." - Robert Big Elk